The Gender Gap Report Part VI: The Rights Perception Divide

How Young Men and Women See Women's Rights Completely Differently

When asked whether women in their country have enough rights, young men and women across Southeast Europe inhabit different realities. Half of young women say women lack sufficient rights, compared to less than three in ten young men. This 22 percentage point gender gap in basic perceptions of rights and equality represents one of the biggest gender-related divides documented in the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung's 2024 Youth Study.

The gap persists across all twelve countries surveyed, though its magnitude varies considerably—from a 34 percentage point chasm in Bosnia and Herzegovina to an 11 point difference in Türkiye. It holds steady across political ideologies, educational levels, and urban-rural divides. And perhaps most tellingly, personal experiences of discrimination amplify rather than bridge this perception gap, with women who face discrimination becoming even more convinced of systemic rights deficits while men's views remain largely unchanged.

This seventh installment in our Gender Gap series examines how young Southeast Europeans assess the state of women's rights—revealing not just different opinions, but different ways of seeing and interpreting gender equality in their societies.

The Basic Reality: A 22 Percentage Point Perception Gap

The numbers are stark. Among Southeast European youth aged 14-29, half of young women (50.6%) believe women in their country do not have enough rights. Only 28.5% of young men share this view—a gap of 22.1 percentage points that represents one of the largest gender divides on any attitude measured in the study.

The inverse pattern holds for other response categories. Over half of young men (55.1%) say women already have enough rights, compared to 42.3% of women. And when it comes to believing women have too many rights, men are more than twice as likely as women to hold this view (16.3% versus 7.1%).

Country Patterns: From Extreme Polarization to Modest Gaps

While the gender gap in rights perceptions appears across all twelve countries, its magnitude varies considerably—revealing different stages or styles of gender attitude polarization across Southeast Europe.

Bosnia and Herzegovina leads the region with the largest perception gap: 57.7% of young women versus only 23.8% of young men believe women lack sufficient rights—a 33.9 percentage point divide. Romania (27.3pp), North Macedonia (27.2pp), and Croatia (27.0pp) show similarly large gaps, all exceeding 25 percentage points.

At the other end of the spectrum, Türkiye shows the smallest gender gap at 10.9 percentage points, though this reflects high baseline concern from both genders (56.6% of women and 45.7% of men see rights deficits). Kosovo (15.5pp) and Slovenia (17.0pp) also show relatively modest gaps, though Slovenia achieves this through low concern from both genders while Kosovo reflects moderate concern across both.

The Full Spectrum of Views

Examining the complete distribution of responses reveals additional complexity beyond the "not enough rights" headline finding.

The "enough rights" middle position attracts pluralities in most countries, particularly among men. In Slovenia, Greece, Kosovo, and Montenegro, roughly 60-70% of young men say women already have enough rights, suggesting satisfaction with the status quo. Young women in these same countries show more divided views, with substantial minorities (or in some cases near-majorities) believing rights remain insufficient.

The "too many rights" position—suggesting backlash or belief that gender equality has gone too far—attracts meaningful minorities of young men in several countries. In Türkiye, Greece, and Montenegro, over 20% of young men believe women have too many rights, compared to single-digit percentages of women. This suggests that for a segment of young men, the issue is not simply satisfaction with current equality but perception that the pendulum has swung too far.

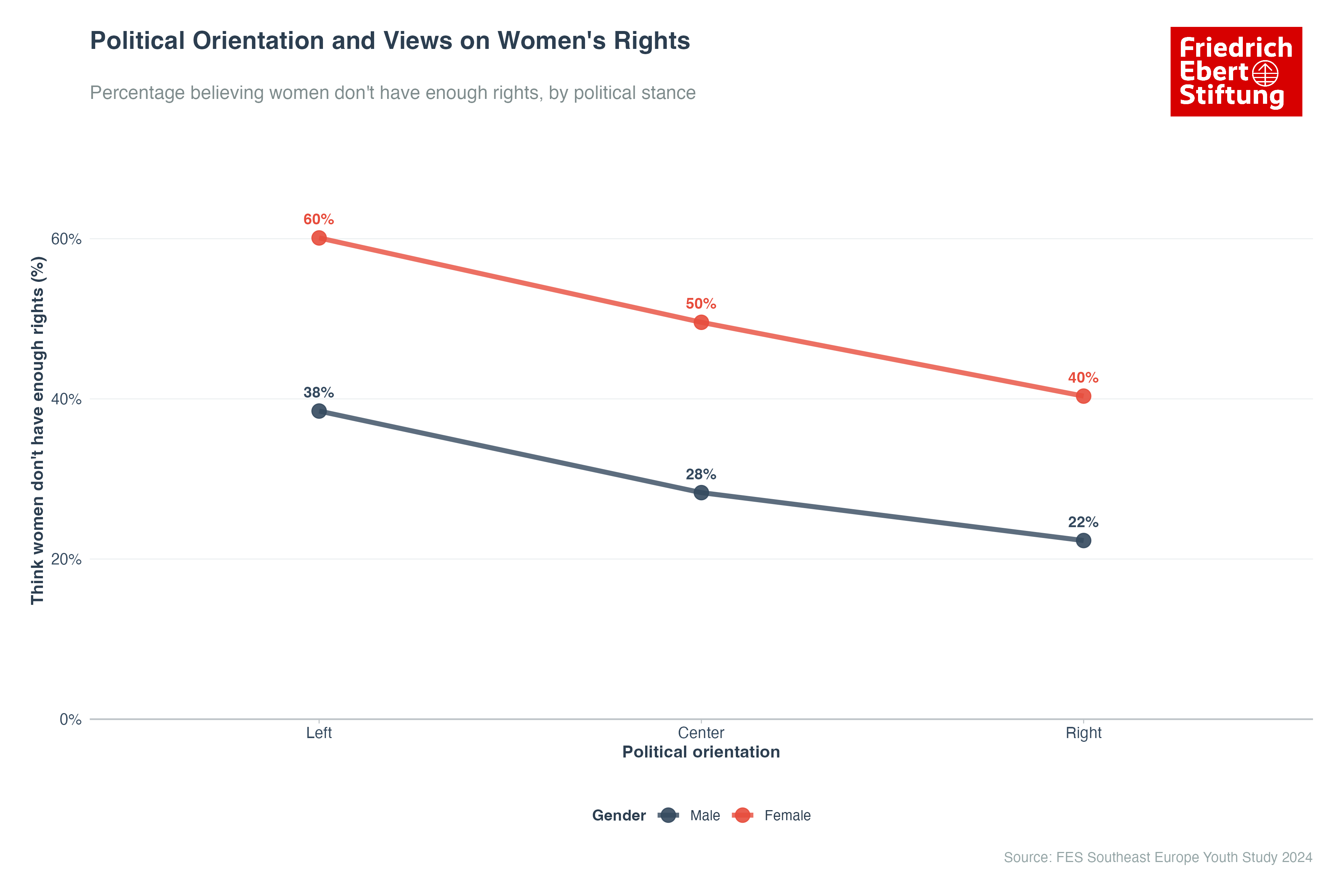

Political Orientation: Consistent Gaps Across the Spectrum

Political ideology shapes baseline views on women's rights but does not eliminate gender gaps—they persist across left, center, and right orientations at remarkably similar magnitudes.

Among left-wing youth, 60.1% of women see rights deficits compared to 38.5% of men—a 21.6 percentage point gap. Among centrists, the gap is nearly identical: 49.6% of women versus 28.3% of men, a 21.3 point difference. Even among right-wing youth, where both genders show lower concern about rights deficits, the gap remains at 18.0 percentage points (40.3% women versus 22.3% men).

The consistency of these gaps across political orientations is interesting. It suggests that gender shapes perceptions of women's rights somewhat independently from broader political ideology. A left-wing young man and a right-wing young woman may disagree about many political issues, but on this question, they likely hold more similar views to each other than to their same-ideology, opposite-gender peers.

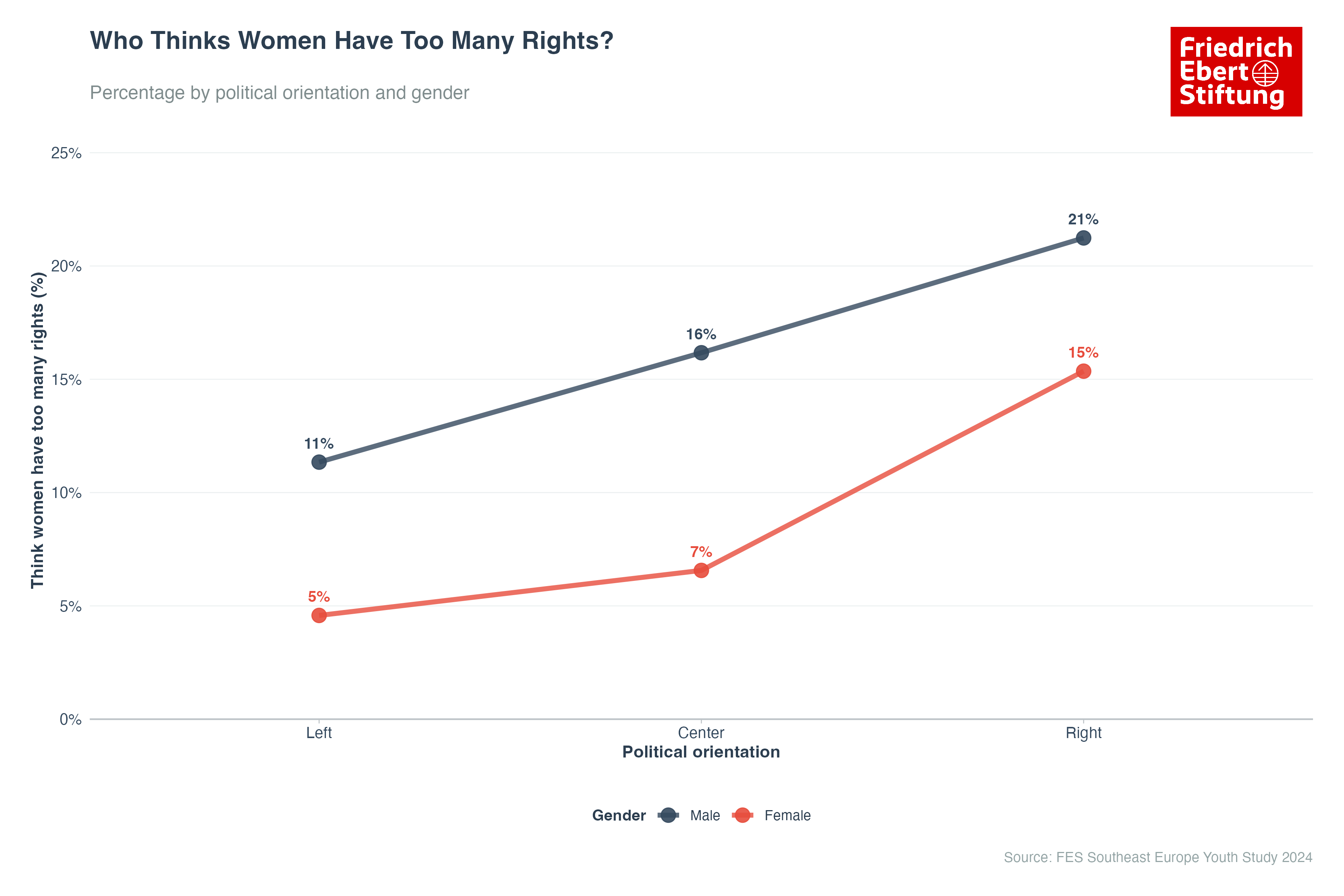

The pattern is similarly consistent for those who believe women have too many rights, though the baseline percentages differ across the political spectrum.

Right-wing men show the highest rates (21.2%) of believing women have excessive rights, compared to 15.4% of right-wing women. But the gender gap persists across all ideological categories, with men consistently more likely than women to perceive rights overreach.

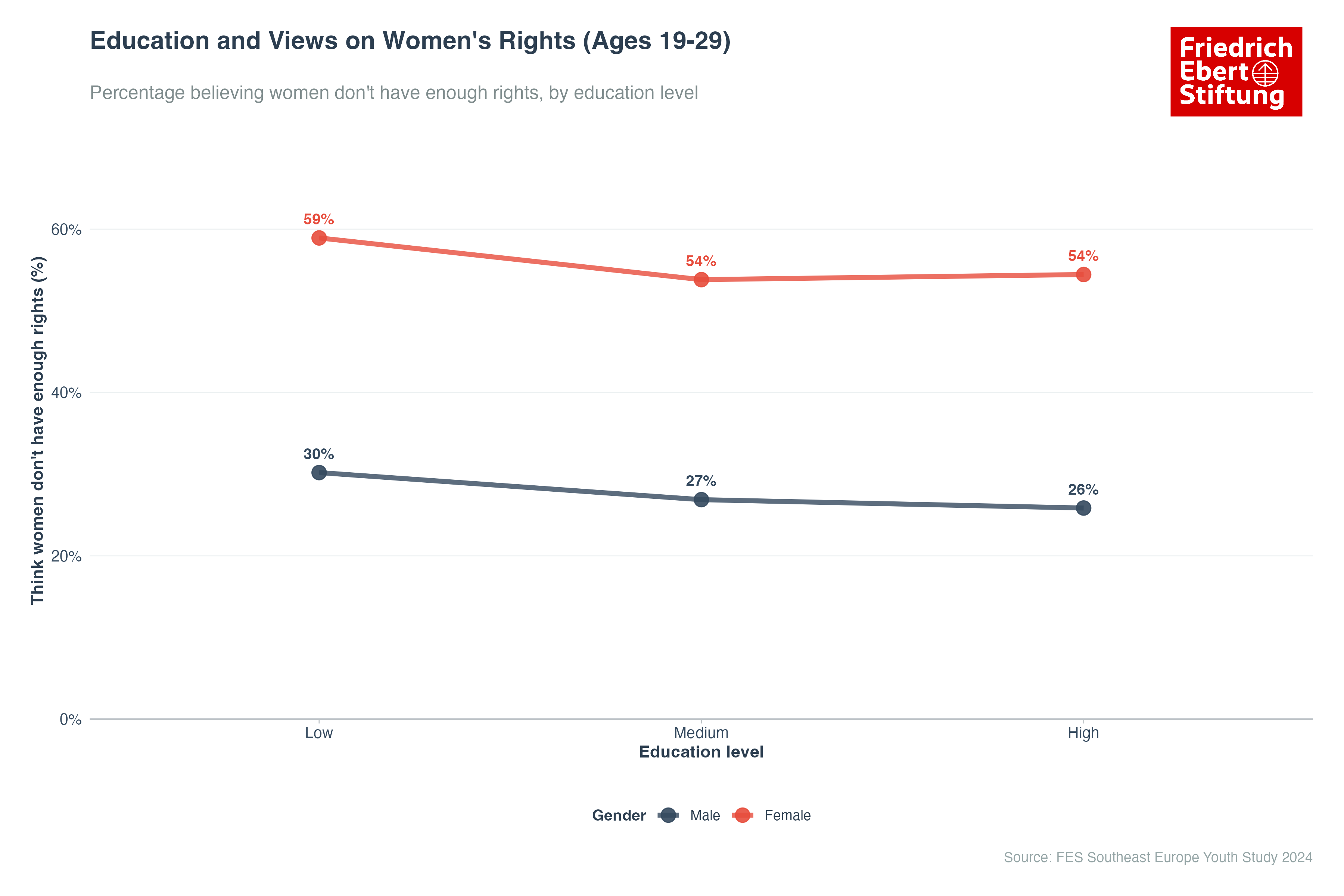

Education: A Non-Factor in the Gender Gap

Education level shows minimal impact on the gender gap in rights perceptions, despite education's strong associations with many other social attitudes.

Among 19-29 year olds with low education, 58.9% of women believe women lack sufficient rights compared to 30.2% of men—a gap of 28.7 percentage points. Among those with high education, the figures are 54.4% of women and 25.9% of men—a gap of 28.6 percentage points. The near-identical magnitude of these gaps suggests education neither bridges nor widens gender differences in rights perceptions.

This pattern differs from many social attitudes where higher education correlates with more liberal or egalitarian views. Here, education may affect overall political and social attitudes, but it does not substantially alter how gender shapes perceptions of women's rights specifically.

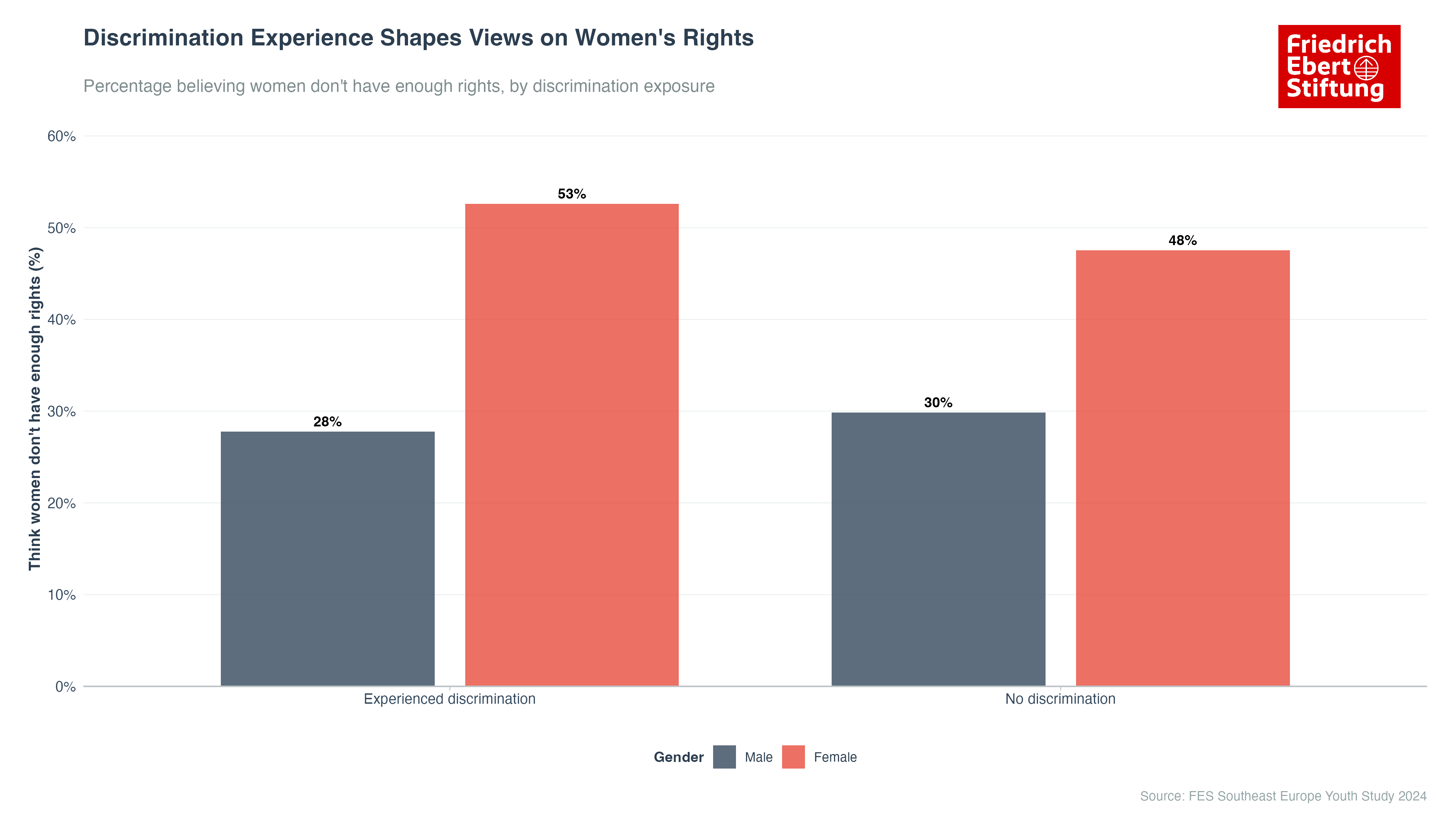

The Discrimination Connection: Experience Amplifies Gender Divides

Personal experiences of discrimination relate to rights perceptions, but in ways that differ by gender.

Among young women who have experienced discrimination of any type, 52.9% believe women lack sufficient rights—5 percentage points higher than among women who have not faced discrimination (47.5%). This increase is statistically significant. For young men, discrimination shows no significant effect: 27.8% of those who experienced discrimination see women's rights as insufficient compared to 29.8% of those who have not, a difference that is not statistically significant.

This pattern reveals that experiences of unfair treatment affect men and women fundamentally differently. Women interpret various forms of discrimination as evidence of broader systemic inequality, while men's discrimination experiences leave their views on women's rights essentially unchanged.

Not All Discrimination Is Equal: Type-Specific Patterns

Gender discrimination is the only type that significantly predicts women's rights beliefs. Among women who experienced gender-based discrimination, 54.3% believe women lack sufficient rights. Other discrimination types—economic, political, ethnic, religious, and language-based—show no statistically significant association with these beliefs, despite similar percentages.

For men, nothing matters. Across all seven discrimination types, the percentage believing women lack sufficient rights stays between 26-28%, regardless of what type of unfair treatment they experienced.

The pattern is simple: experiencing sexism makes women more aware of gender inequality. Experiencing other forms of discrimination doesn't. And for men, experiencing any form of discrimination—including gender-based—doesn't change their views on women's rights at all.

The Intersectional Picture: How Experience and Politics Combine

When discrimination experience and political orientation are examined together, three statistically significant patterns emerge.

Among left-wing women, discrimination experience creates the largest effect: 65% of those who faced discrimination see women's rights as insufficient compared to 53% without such experience. Center women show a similar pattern: 52% versus 45%. For progressive and centrist women, discrimination experiences heighten awareness of gender inequality.

Right-wing women show no significant effect (39% versus 42%), and left or center men show no significant effects either. But right-wing men display the chart's most interesting finding: those who experienced discrimination are far less likely to see women's rights as insufficient (19%) compared to those without such experience (31%)—a 12 percentage point drop that is significant.

This suggests that for conservative men, personal experiences of unfair treatment actually reduces sympathy for women's rights claims, perhaps by framing equality as a zero-sum competition for victim status rather than creating solidarity across different forms of inequality.

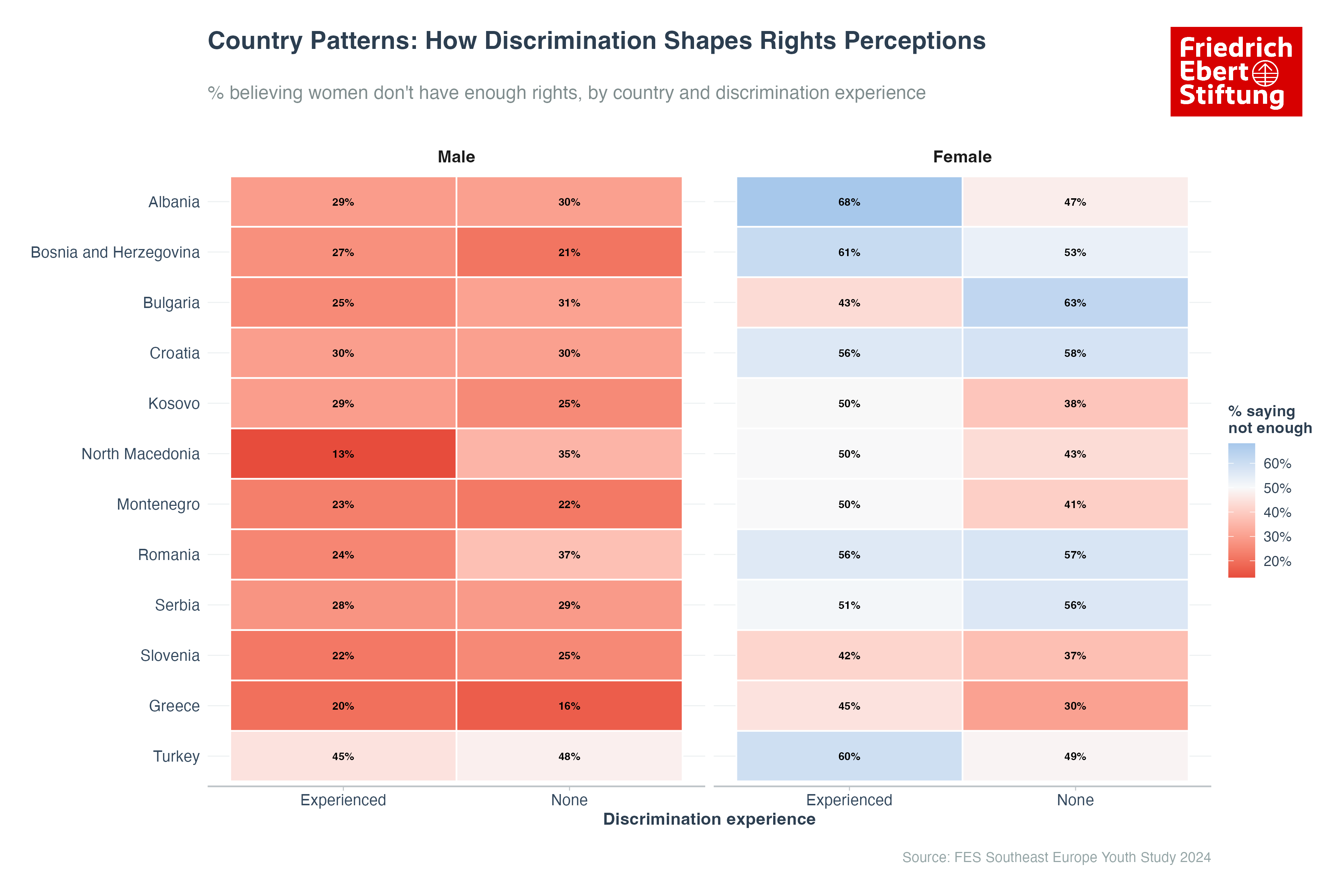

Country-Level Patterns: Discrimination Amplifies National Divides

Discrimination experiences significantly affect women's rights perceptions in only five of twelve countries—but where effects exist, they are substantial.

In Albania, Kosovo, Greece, and Türkiye, discrimination experiences significantly increase the percentage of women who see rights deficits. Albania shows the largest effect: women with discrimination experience are 21 percentage points more likely to see rights as insufficient (68% versus 47%). Greece shows a similarly strong pattern (45% versus 30%), despite the earlier characterization of its gender gap as modest.

Bulgaria stands out with a counterintuitive reverse pattern: women who experienced discrimination are significantly less likely to see women's rights as insufficient (43% versus 63%). The reason for this is unclear and warrants further investigation. It is not explained by differences in discrimination type prevalence, as Bulgarian women experience gender discrimination at above-average rates compared to other countries in the study.

For men, two countries show significant patterns—both decreases in concern. In North Macedonia and Romania, men who experienced discrimination are significantly less likely to believe women lack rights (similar to the right-wing men pattern observed earlier). Most countries show no significant discrimination effects for men.

Who Experiences What: The Demographics of Discrimination

An important context for understanding these patterns is that men and women experience different types of discrimination at different rates across the region.

Gender discrimination is the only type more commonly reported by women than men (33.9% of women versus 23.0% of men). All other forms of discrimination are more commonly reported by men: political discrimination (34.2% men vs 26.4% women), economic (40.5% vs 37.3%), religious (30.9% vs 25.0%), ethnic (28.6% vs 21.2%), language (29.4% vs 22.6%), and sexual orientation (17.4% vs 12.9%).

This means that despite men experiencing more discrimination overall across most categories, women are much more likely to connect their experiences—particularly gender discrimination but also other types—to beliefs about systemic gender inequality. The issue is not the quantity of discrimination experiences but their interpretation and the conclusions drawn from them.

What Explains the Perception Gap?

Several factors likely contribute to the persistent gender gap in rights perceptions across Southeast Europe:

Different Stakes: Women may be more attuned to rights deficits because they affect them directly. What men perceive as abstract questions about equality, women experience as concrete limitations on their opportunities, safety, or autonomy. This asymmetry in personal stakes likely drives some of the perception difference.

Visibility of Inequality: Gender-based constraints and discrimination may be more visible to those who experience them. Subtle forms of bias, everyday sexism, or structural barriers that women navigate regularly may be largely invisible to men who do not face them, leading to genuine disagreement about whether problems exist.

Different Baselines: Men and women may use different reference points for evaluating women's rights. Men might compare current conditions to past decades and see progress, while women compare current conditions to male experiences and see continued gaps. These different comparison frameworks can yield different conclusions about whether rights are sufficient.

Motivated Reasoning: Some gender differences may reflect motivated reasoning, where existing advantages (for men) or disadvantages (for women) shape perceptions in self-interested directions. However, the consistency of gaps across political ideologies and the fact that many men do recognize rights deficits suggests this is not purely about self-interest.

Social Movements and Awareness: The rise of feminist movements, #MeToo, and increased public discussion of gender issues may have raised consciousness about persistent inequalities, particularly among women. Men may be less exposed to or engaged with these discussions, maintaining older frameworks for thinking about gender equality.

Implications for Gender Equality Advocacy and Policy

The massive perception gap documented here presents both challenges and insights for those working toward gender equality in Southeast Europe:

The Consensus Problem: Building public support for new women's rights measures faces a fundamental challenge: roughly half of the population may not see the need for additional protections or reforms. This perception gap must be addressed before policy change can gain broad backing.

Beyond Information Deficits: The fact that education does not eliminate the perception gap suggests this is not simply an information problem that can be solved through better communication. Gender appears to create different interpretative frameworks that shape how the same information is understood and evaluated.

The Discrimination Paradox: Men's discrimination experiences—even experiencing gender discrimination themselves—do not increase their concern about women's rights. This suggests that awareness campaigns focused on highlighting discrimination or injustice may have limited effectiveness in shifting men's views. Simply making problems "visible" is insufficient when the fundamental issue is how experiences are interpreted rather than whether they are seen.

Political Cross-Cutting: The consistency of gender gaps across political ideologies suggests that women's rights advocacy might benefit from cross-partisan approaches that recognize this as a gender issue that cuts across traditional left-right divides, rather than treating it solely as a progressive political issue.

The Right-Wing Challenge: The finding that right-wing men who experience discrimination become less sympathetic to women's rights suggests that for some groups, equality advocacy may trigger defensive or competitive reactions. Strategies that frame gender equality as threat or competition are likely to backfire with these audiences.

Country-Specific Challenges: The substantial variation across countries—with discrimination effects significant in only five of twelve—indicates that one-size-fits-all regional approaches may be less effective than country-specific strategies.

Conclusion: Bridging the Perception Divide

Young men and women across Southeast Europe look at their societies and see fundamentally different realities when it comes to women's rights. Half of young women believe women lack sufficient rights; less than three in ten young men agree. This is not a minor disagreement or a marginal divide—it is a chasm in basic perceptions of equality that appears across countries, political ideologies, and educational levels.

The persistence and consistency of this gap raise important questions about the path to gender equality in the region. How can societies make progress on gender issues when roughly half the population sees problems that the other half does not recognize as existing? How can women's rights advocates build coalitions for change when the need for change itself is contested?

The findings on discrimination add another layer of complexity: experiences of unfair treatment lead women to heightened awareness of systemic gender inequality while leaving men's views largely unchanged. This suggests that making injustice visible is necessary but not sufficient for building consensus—there must also be shared frameworks for interpreting those experiences and connecting them to broader patterns of inequality.

Perhaps the most challenging implication is that the gender perception gap may be self-reinforcing. As women become more convinced that rights deficits exist, they may become more vocal about gender issues. If men interpret this advocacy as overreach rather than response to genuine problems, the "too many rights" perspective may gain ground, further polarizing attitudes. Breaking this cycle requires not just better policies but better ways of building shared understanding across the gender divide.

The path forward is more challenging than simply raising awareness. Since even personal experiences of discrimination do not shift men's views, the problem runs deeper than visibility or information. Progress may require fundamentally rethinking how gender equality is framed and communicated—moving beyond appeals to fairness or shared experiences of injustice, which the data suggests are ineffective with large segments of the male population.

Above all, these findings suggest that achieving gender equality in Southeast Europe will require not just changing laws and institutions, but bridging the fundamental perception divide about whether change is needed at all. Until young men and women can look at their societies and see more similar realities, progress on women's rights will face persistent headwinds from those who simply do not see the problems that half the population experiences daily.

About the Data

This analysis draws from the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung's Southeast Europe Youth Study 2024, examining attitudes among 8,943 young people aged 14-29 across Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Romania, Serbia, Slovenia, Greece, and Türkiye. The question analyzed asked: "Do women in your country have enough rights?" Discrimination experiences were measured across seven types: gender, economic, religious, ethnic, political, sexual orientation, and language-based discrimination.

Related publication

Hasanović, Jasmin ; Lavrič, Miran ; Adilović, Emina ; Stanojević, Dragan

Youth study Southeast Europe 2024

independent but concerned: the voices of young people in Southeast Europe